The Human Cost of Environmental Data Mismanagement: Lessons from Film and History

Environmental data may seem abstract, but when it comes to environmental pollution or sustainability, they can be a matter of life and death.

Environmental data may seem abstract, but when it comes to environmental pollution or sustainability, they can be a matter of life and death.

By 1992, Duplan and Buckle weren’t just theorizing about AI and automation systems – they were implementing these concepts through the ITEMS.

The vision of an integrated Environmental Data Management System that automated data handling from field to lab to report generation.

Discover the top 10 features that water utilities should prioritize when selecting modern water management software.

The EPA set a course of action for addressing PFAS in drinking waters. Attention is turning to industrial and municipal wastewaters.

At Locus, we empower global enterprises to shift from passive compliance to strategic ESG leadership with corporate sustainability software.

Reflecting on Marian Carr’s 22 years at Locus Technologies.

At Locus, our Environmental Information Management (EIM) system stores an extensive array of data locations, field samples…

Locus Technologies Scales Its EHS Information Platform; Adding Clients, Regions & Seamless Integration

Neno Duplan, Founder & CEO. Dr. Duplan is a pioneer in environmental information management and cloud-based sustainability solutions. As the founder and CEO of Locus Technologies, he has nearly 30 years of experience applying advanced computing to environmental, water, and energy industries. Locus has become a global leader in on-demand environmental data management, helping organizations track and comply with sustainability and regulatory requirements. Dr. Duplan continues to drive cloud and AI-powered innovations for sustainability, ensuring companies can efficiently manage emissions, water, and compliance data.

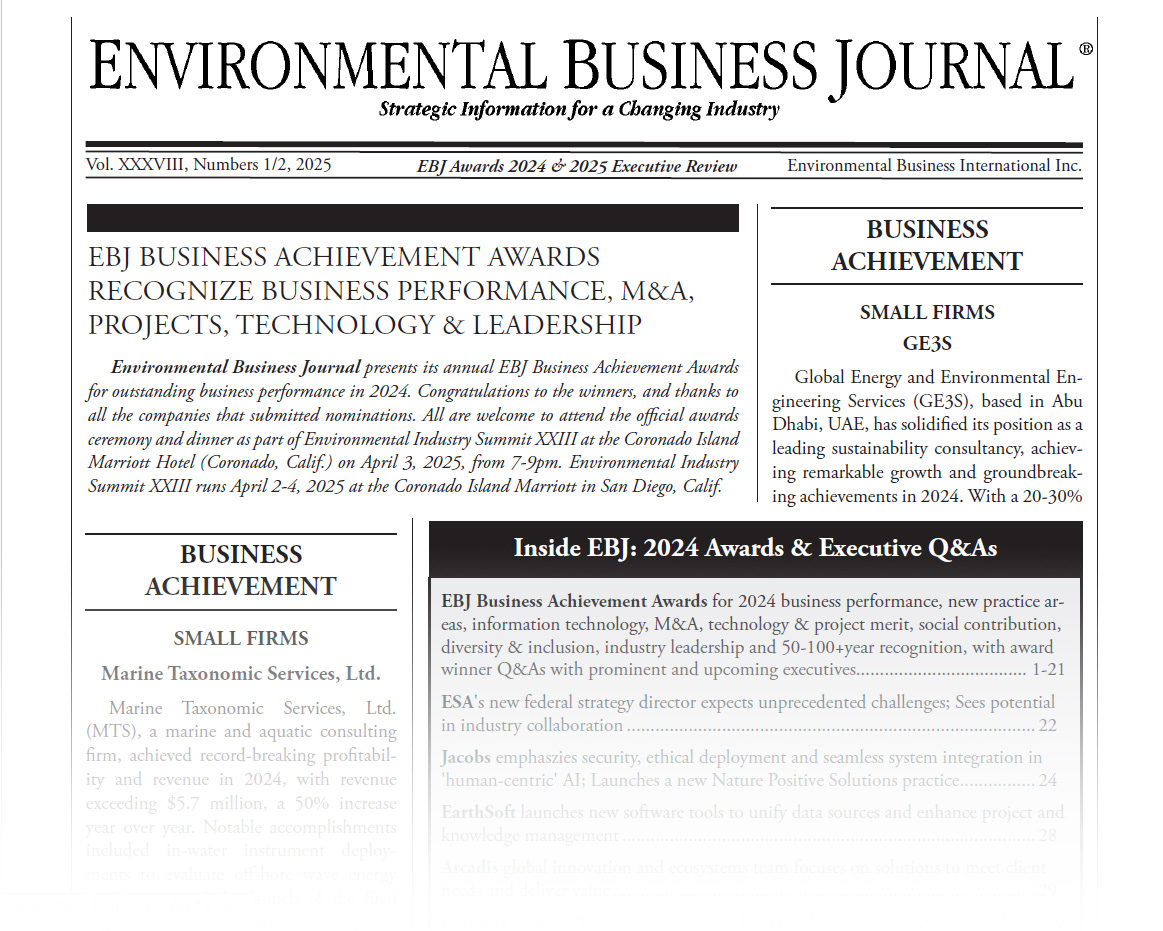

Environmental Business Journal, Volume 38 Numbers 1/2: Q1 2025

EBJ Awards 2024 & 2025 Executive Review

Inspections and audits are a critical aspect of various sectors, including safety, waste management, environmental compliance, construction, etc.

Locus Technologies » Applications » Sustainability » ESG » Page 6

299 Fairchild Drive

Mountain View, CA 94043

P: +1 (650) 960-1640

F: +1 (415) 360-5889

Locus Technologies provides cloud-based environmental software and mobile solutions for EHS, sustainability management, GHG reporting, water quality management, risk management, and analytical, geologic, and ecologic environmental data management.