5 Ways to Manage Your Hazardous Waste

The Locus Waste Management application enables EHS professionals to manage wastes across their entire enterprise and prepare reports with just one click.

The Locus Waste Management application enables EHS professionals to manage wastes across their entire enterprise and prepare reports with just one click.

In August 2014, we wrote on the potential use of wearables for EHS professionals. Less than a year later, the Apple Watch was introduced, revolutionizing the market. Now, wearables in the EHS space aren’t a hypothetical. Roughly a fifth to a quarter of Americans wear a smartwatch daily. Wearables are undoubtedly one of the biggest trends in EHS, with a seemingly endless number of uses to promote a more efficient and safer workplace.

Despite recent growth, wearables are still in their infancy when it comes to EHS. Verdantix anticipates that companies will spend 800% more on connected worker devices in twenty years, an explosion in utilization. This year alone, over 20% of surveyed companies are reporting an increase in budget for wearables for EHS purposes. While demand from organizations is growing, most EHS software is yet to adapt to market needs, with few offering wearable support.

Locus is prepared to meet the needs of the market, by integrating wearable support with our mobile application. Here are a few ways to best utilize your smartwatch with Locus Mobile:

Custom and priority notifications can be tailored to fit the needs of professionals in your organization, increasing engagement and response time.

Calendar alerts directly to your wearable, so that no samples are missed by field technicians.

Get alerted when you’re entering a safety zone that requires specific PPE.

Track worker vital signs for faster response time in the event of an emergency.

If your organization is looking to implement wearable tech, Locus product specialists are ready to discuss your needs and how we can help.

The recent year of lockdowns pushed many daily activities into the virtual world. Work, school, commerce, the arts, and even medicine have moved online and into the cloud. As a result, considerably more resources and information are now available from an internet browser or from an application on a handheld device. To navigate through all this content and make sense of it, you need the ability to quickly search and get results that are most relevant to your needs.

You can think of the web as a big database in the cloud. Traditionally, database searches were done using a precise syntax with a standard set of keywords and rules, and it can be hard for non-specialists to perform such searches without learning programming languages. Instead, you want to search in as natural a matter as possible. For example, if you want to find pizza shops with 15 miles of your house that offer delivery, you don’t want to write some fancy statement like “return pizza_shop_name where (distance to pizza shop from my house < 15 miles) and (offers_delivery is true). You just want to type “what pizza shops within 15 miles of my house offer delivery?” How can this be done?

Enter the search engine. While online search engines appeared as early as 1990, it wasn’t until Yahoo! Search appeared in 1995 that their usage became widespread. Other engines such as Magellan, Lycos, Infoseek, Ask Jeeves, and Excite soon followed, though not all of them survived. In 1998, Google hit the internet, and it is now the most dominant engine in use. Other popular engines today are Bing, Baidu, and DuckDuckGo.

Current search engines compare your search terms to proprietary indexes of web page and their content. Algorithms are used to determine the most relevant parts of the search terms and how the results are ranked on the page. Your search success depends on what search terms you enter (and what terms you don’t enter). For example, it is better to search on ‘pizza nearby delivery’ than ‘what pizza shops that deliver are near my house’, as the first search uses less terms and thus more effectively narrows the results.

Search engines also support the use of symbols (such as hyphens, colons, quote marks) and commands (such as ‘related’, ‘site’, or ‘link’) that support advanced searches for finding exact word matches, excluding certain results, or limiting your search to certain sites. To expand on the pizza example, support you wanted to search for nearby pizza shops, but you don’t want to include Nogud Pizza Joints because they always put pineapple on your pizza. You would need to enter ‘pizza nearby delivery -nogud’. In some ways, with the need to know special syntax, searching is back where it was in the old database days!

Search engines are also a key part of ‘digital personal assistants’, or programs that not only perform searches but also perform simple tasks. An assistant on your phone might call the closest pizza shop so you can place an order, or perhaps even login to your loyalty app and place the order for you. There is a dizzying array of such assistants used within various devices and applications, and they all seem to have soothing names such as Siri, Alexa, Erica, and Bixby. Many of these assistants support voice activation, which just reinforces the need for natural searches. You don’t want to have to say “pizza nearby delivery minus nogud”! You just want to say “call the nearest pizza shop that does delivery, but don’t call Nogud Pizza”.

Search engine and digital personal assistant developers are working towards supporting such “natural” requests by implementing “natural language processing”. Using natural language processing, you can use full sentences with common words instead of having to remember keywords or symbols. It’s like having a conversation as opposed to doing programming. Natural language is more intuitive and can help users with poor search strategies to have more successful searches.

Furthermore, some engines and assistants have artificial intelligence (AI) built in to help guide the user if the search is not clear or if the results need further refinement. What if the closest pizza shop that does delivery is closed? Or what if a slightly farther pizza place is running a two-for-one special on your favorite pizza? The built-in AI could suggest choices to you based on your search parameters combined with your past pizza purchasing history, which would be available based on your phone call or credit charge history.

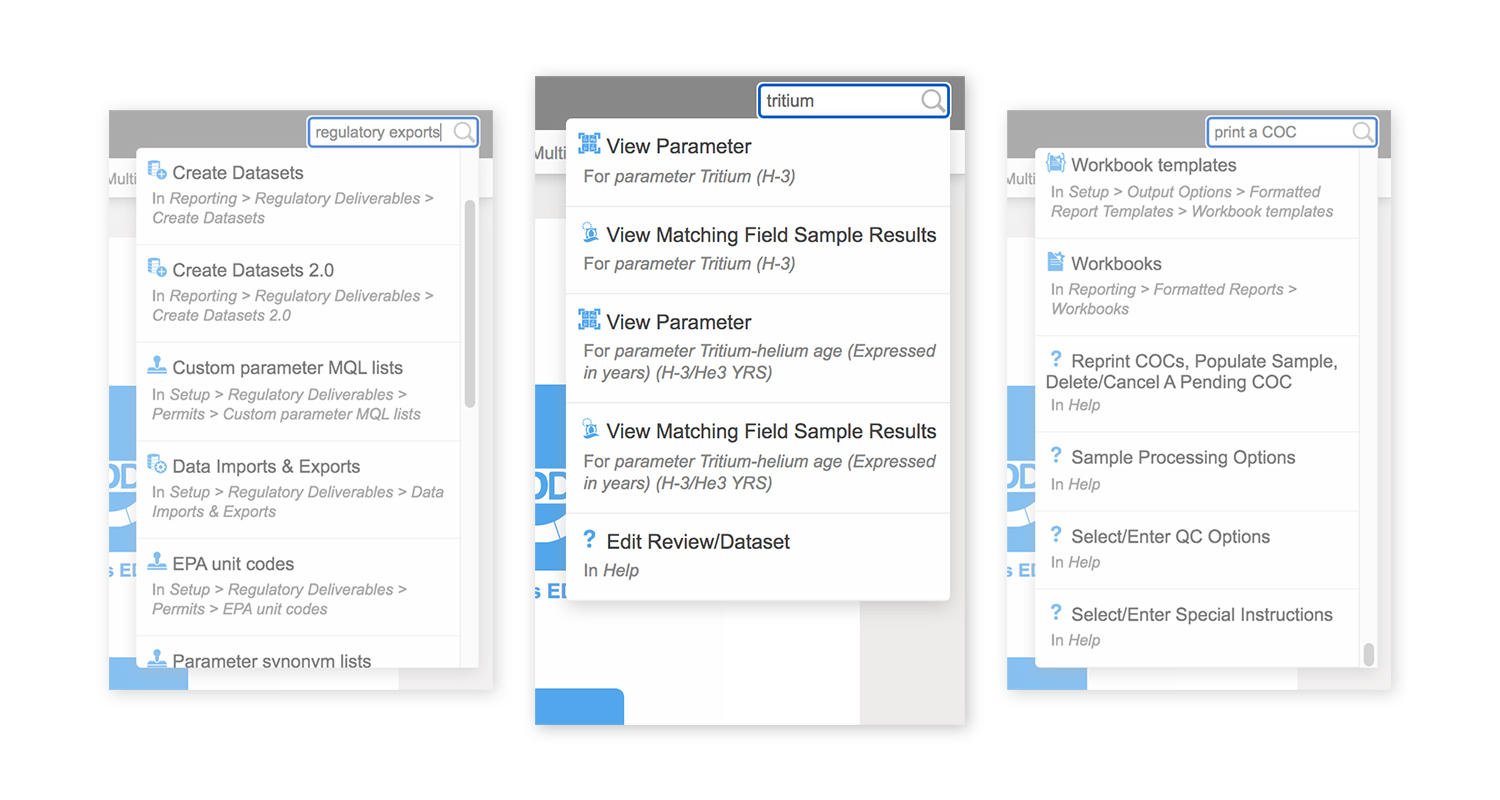

The Locus team recently expanded the functionality of the EIM (Environmental Information Management) search bar to support different types of data searches. If a search term fits several search types, all are returned for the user to review.

EIM lets the user perform successful searches through various methods. In all searches, the user does not need to specify if the search term is a menu item, help page, or data entity such as parameter or location. Rather, the search bar determines the most relevant results based on the data currently in EIM. Furthermore, the search bar remembers what users searched for before, and then ranks the results based on that history. If a user always goes to a page of groundwater levels when searching for location ‘MW-1’, then that page will be returned first in the list of results. Also, the EIM search bar supports common synonyms. For example, searches for ‘plot’, ‘chart’, and ‘graph’ all return results for EIM’s charting package.

By implementing the assistance methods described above, Locus is working to make searching as easy as possible. As part of that effort, Locus is working to add natural language processing into EIM searches. The goal is to let users conduct searches such as ‘what wells at my site have benzene exceedances’ or perform tasks such as ‘make a chart of benzene results’ without having to know special commands or query languages.’

How would this be done? Let’s set aside for now the issues of speech recognition – sadly, you won’t be talking to EIM soon! Assume your search query is ‘what is the maximum lead result for well 1A?’

A similar process could be done for tasks such as ‘make a chart of xylene results’. In this case, however, there is too much ambiguity to proceed, so EIM would need to return queries for additional clarifications to help guide the user to the desired result. Should the chart show all dates, or just a certain date range? How are non-detects handled? Which locations should be shown on the chart? What if the database stores separate results for o-Xylene, m,p-Xylene, plus Xylene (total)? Once all questions were answered, EIM could generate a chart and return it to the user.

Natural language is the key to helping users construct effective searches for data, whether in EIM, on a phone, or in the internet. Locus continues to improve EIM by bringing natural language processing to the EIM search engine.

About the Author—Dr. Todd Pierce, Locus Technologies

Dr. Pierce manages a team of programmers tasked with development and implementation of Locus’ EIM application, which lets users manage their environmental data in the cloud using Software-as-a-Service technology. Dr. Pierce is also directly responsible for research and development of Locus’ GIS (geographic information systems) and visualization tools for mapping analytical and subsurface data. Dr. Pierce earned his GIS Professional (GISP) certification in 2010.

Recently, Locus CEO Neno Duplan described the need for credible ESG Reporting, and the evolving corporate, financial, and political drivers leading to the proliferation of ESG reporting. Here, we look at some of the practical aspects of building and maintaining an ESG reporting program. After leading audits for greenhouse gas emissions and other ESG metrics for the past ten years, I wanted to highlight the pitfalls that many organizations face when it comes to supporting their ESG reports, and provide some solutions to improve their auditability.

With the current wave of popularity for Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting, many organizations are scrambling to assemble reports that cover these metrics. While a spreadsheet can be readily put together with enterprise-level totals for emissions, resource consumption, community involvement and other metrics, most of those reports won’t stand up to a full audit process. And increasingly savvy investors and stakeholders aren’t necessarily willing to take these reports at face value.

Whether you are getting started on a new ESG reporting program for your organization, or transforming an existing CSR program to cover ESG elements, it is critical to plan ahead for ensuring your final report is audit-ready. That means not only maintaining full visibility for the raw data, calculations, and various factors that went into the report, but also making that data easily accessible and traceable. Consider the case where a stakeholder is comparing two ESG reports where the overall metrics are similar. But one of the reports has a fully transparent data flow back to the source, and the other report can only be verified through a lengthy documentation request to a consultant. Although the final reports may be similar, the stakeholder gains more trust with less effort when the supporting data is readily available.

There is quite a bit of uncertainty over how comprehensive ESG audits should be. Current audit protocols for ESG reporting vary widely. Organizations like the Center for Audit Quality have put forth guidance on how ESG reports could be audited. However, there are no strict requirements and little consensus on what should or should not be included in the audit of an ESG report. Established reporting frameworks like GRI, SASB, and TCFD have programs in place for assurance of those reports, which include a third-party audit for the accuracy and completeness of that data. However, organizations have the choice of achieving either limited assurance or reasonable assurance, and they may choose to have only select metrics or disclosures audited, or they may opt to undergo a more thorough examination that covers the full report. That flexibility is likely to change, however, as stakeholders apply additional pressure for better quality and reliability in ESG reports.

So how do you go about developing an ESG program that can meet current and potential future audit requirements? Based on my auditing experience, here are a few key concepts to keep in mind:

Centralize your data flow, with consistent data quality controls. A unified data collection program is key to streamlining the audit process and having greater confidence in your report. Historically, reporting for ESG has been the responsibility of multiple departments with little intercommunication. The result of that separation is widely different practices when it comes to assuring data quality. Integrations between systems can help and are sometimes the best option to bring together data from different sectors of the ESG report. But ultimately, a consistent approach to the overall data collection and processing effort will result in a much smoother (and cheaper) audit.

Automate data collection wherever possible. Auditors know that manual data entry or transcription is typically one of the major weak points in any data collection program. We’re trained to focus in on those parts of the process with additional data sampling and review to find errors. If you have any opportunities to collect data through automated tools or direct connections to reliable data sources, those tools are the quickest ways to shore up those potential weaknesses, and also have the benefit of substantially reducing your ESG data collection effort.

Maintain documentation throughout the data collection process. During one audit years ago, I asked the reporter for their documentation on their electricity consumption, and they pointed to a scribbled sticky note on their wall. Of course, that didn’t quite suffice for audit purposes, and neither does an email from a co-worker, or any number of other data sources that reporters have tried to pass off as their documentation. For inputs that derive from sources outside your organization, like utility invoices or supplier surveys, data are considered more reliable if they are directly tied to a financial transaction between entities that do not share ownership. The general thought is that if the data quality was considered sufficient to exchange money based on the value, it can be considered reasonably accurate. If that is not the case, ideally an attestation, or at least the source’s contact information, should be maintained for each data source. For data inputs derived from internal sources (e.g. meter readings), the documentation will need to include the data itself, as well as information on the devices used and their maintenance (e.g. calibration records).

Given the many issues with spreadsheet data handling including lack of unification, security, and error proliferation and persistence, many organizations are correctly concluding that a dedicated software application provides numerous process improvements for ESG reporting. But unfortunately there are many software tools that take the input data and generate an ESG report with little or no visibility into how the input data were processed or calculated. And to an auditor, those part of the process are critical to achieving assurance for an ESG report. Sometimes the data processing steps can be viewed, but they’re buried within the configuration settings and require navigation by a system administrator to extract. In this situation, auditors can try to replicate the calculations from the raw data on their own, and attempt to yield the same results. This approach can work for many accounting metrics, which are largely standardized, and easily replicable from the input data. However, other metrics like Scope 3 emission calculations can follow a number of different methodologies with different factors. Without knowing which methods and factors were used, the auditor is unlikely to yield the same results. Having a transparent calculation engine that can visualize the data flow and processing can make a huge difference when it comes to your audit.

Assembling an ESG reporting program is a significant undertaking, and it may be a monumental effort to simply get the report done, especially if you’re just getting your program started. But to fully set yourself up for long-term success, be sure to assess the audit readiness of your ESG program. Even though ESG auditing is not yet fully codified, more formalized audit protocols are expected soon. Some simple considerations early in your program development will make sure you are prepared for whatever those audit requirements may include.

About the Author—J. Wesley Hawthorne, President of Locus Technologies

Mr. Hawthorne has been with Locus since 1999, working on development and implementation of services and solutions in the areas of environmental compliance, remediation, and sustainability. As President, he currently leads the overall product development and operations of the company. As a seasoned environmental and engineering executive, Hawthorne incorporates innovative analytical tools and methods to develop strategies for customers for portfolio analysis, project implementation, and management. His comprehensive knowledge of technical and environmental compliance best practices and laws enable him to create customized, cost-effective and customer-focused solutions for the specialized needs of each customer.

Mr. Hawthorne holds an M.S. in Environmental Engineering from Stanford University and B.S. degrees in Geology and Geological Engineering from Purdue University. He is registered both as a Professional Engineer and Professional Geologist, and is also accredited as Lead Verifier for the Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Low Carbon Fuel Standard programs by the California Air Resources Board.

299 Fairchild Drive

Mountain View, CA 94043

P: +1 (650) 960-1640

F: +1 (415) 360-5889

Locus Technologies provides cloud-based environmental software and mobile solutions for EHS, sustainability management, GHG reporting, water quality management, risk management, and analytical, geologic, and ecologic environmental data management.